- Home

The BlogLearn MoreSoda SpringsTips for WritersCivil RightsMore Info

|

Martin Luther King in '63:

Birmingham's Civil Rights Movement

Dr. Martin Luther King captured the nation's headlines in the spring and summer of 1963 when he joined the Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham, Alabama -- a place he called "the most segregated city in America."

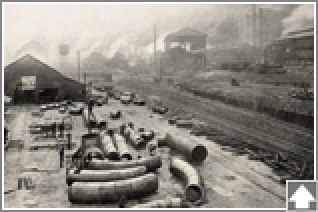

Birmingham, Alabama's largest city -- 350,000 residents in 1960 -- owed its economy to a rarity of nature . . . its hills held all the ingredients of steel: iron ore, coal, and limestone.

Birmingham owed its rapid growth as the South's first industrial city to a unique institution of the Old Confederacy: the convict lease. The state hired out half its convicts -- many arrested for such crimes as gambling, indebtedness, and idleness -- to private industry. In Birmingham, that meant to the tuberculosis-plagued coal mines. The mines kept their workers in line with beatings, bloodhounds, and sometimes, death. The state got revenue, and industry got a cheap, strike-proof labor force . . . primarily Negro.

Through the years, the convict lease fell out of use . . . replaced by low wages and fueled by a constant influx of poor, rural Negroes into the city.

In 1960, 40 percent of Birmingham's residents were Negro. They were at the bottom of the economic, social, and political totem poles:

- Ten percent of those eligible were registered voters.

- Negroes held the lowest-paid labor jobs.

- Schools and public facilities were segregated.

- Elected officials and city employees were white, and they maintained their dominant position with an iron hand.

- More than 50 unsolved bombings remained on the police department books, mostly Negro churches and homes of Negro residents.

Unknown to Rick Sanders and Charlie McPherson, the city of Birmingham was in a political turmoil when they blew into town on April 6 for spring vacation; they knew nothing of local politics.

On April 2, Birmingham voters had elected a new mayor and city council. But the defeated mayoral candidate, Eugene "Bull" Connor, the city police commissioner, and his cronies, the ousted city council, refused to give up their offices. Physically! They wouldn't leave. The bizarre turn of events was headed into the courts.

The next day, on April 3, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, led by Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, issued a manifesto demanding

- desegregated public facilities: downtown toilets • water fountains • lunch counters • store dressing rooms • city parks;

- hiring of Negro store clerks (there were none);

- fair hiring practices in all city departments (the city had no Negro policemen or firemen);

- a biracial committee to work toward desegregating the schools.

To press their demands, Rev. Shuttlesworth's organization that same day began a direct action campaign: groups of Negroes boldly walked up to the all-white lunch counters at four downtown stores, sat down, and asked for service.

The police responded unequivocally: they jailed 20 demonstrators.

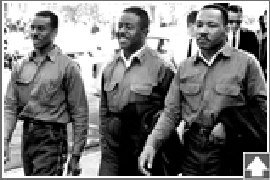

That same day, Rev. Martin Luther King and Rev. Ralph Abernathy flew into Birmingham to lend a hand based on their experience in their successful Montgomery bus boycott of seven years earlier. In Negro Birmingham, nightly rallies began, rotating among the city's Negro churches.

The following is a timeline of events that form the backdrop to Soda Springs:

Prelude to Birmingham's summer of 1963

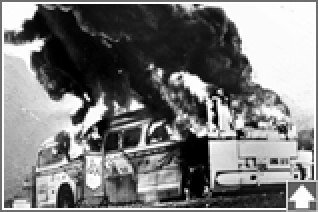

May 14, 1961 (Mother's Day):

Near Anniston, Alabama, a white mob burns one of two Freedom Rider buses en route to Birmingham. Another mob attacks and beats the riders upon arrival in Birmingham. From Birmingham, the Freedom Riders fly on to New Orleans rather than continue their trip by bus.

Week of March 14, 1962:

Blacks begin boycott of downtown Birmingham stores, led by Lucius Pitts of Miles College. The boycott fails.

Birmingham's Spring of '63

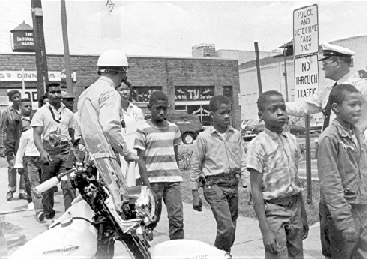

April 2, Tuesday: Birmingham city election. Police commissioner Bull Connor loses mayor's race to Albert Boutwell. New city council elected. Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, founder of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), a Birmingham organization that will spearhead the coming protests, issues the "Birmingham Manifesto," a list of demands for ending segregation in Birmingham. He had postponed the beginning of his "Project C" (for confrontation) until after the election so as not to create a white backlash that would help Bull Connor win the mayor's race. April 3, Wednesday: Lunch counter sit-ins at four different stores: Woolworth's, Loveman's, Pizitz, Kress, i.e. blacks sitting in traditionally all-white sections. 20 arrested. Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) fly into Birmingham. They headquarter at the A.G. Gaston Motel on 5th Ave near Kelly Ingram Park. It's the only motel in town that accepts Negroes. 6 p.m.: opening meeting of the Birmingham campaign at St. Jones Baptist Church, Rev. Ed Gardner presiding. Rev. Martin Luther King, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, and Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth all speak. April 4, Thursday: ACMHR issues press release on objectives for its Project C campaign. Mayor Boutwell denounces civil rights activists as "outsiders." The 20 demonstrators arrested the prior day go on trial, are found guilty, and given 180 days in jail plus $100 fines. They'll work in Bull Connor's prison farm and laundry. Four demonstrators arrested at Lane-Liggett Drug Store sit-in. 500 people rally at St. Jones Baptist Church that night. April 5, Friday: 10 activists are arrested at sit-ins at the elegant Tutwiler Hotel and the Lane-Liggett Drug Store. April 6, Saturday: Rev. Shuttlesworth leads a group of marchers from the Gaston Motel into white Birmingham. The police stop them at the federal building and arrest 29, including Shuttlesworth. This is the first protest march of the Birmingham campaign. It consists of 45 men and women, all dressed smartly in their Sunday church attire. April 7, Sunday (Palm Sunday): Alabama Gov. George Wallace orders the state director of public safety to send state patrolmen to Birmingham.

April 8, Monday: Martin Luther King meets with 200 Birmingham black ministers. (Note: eventually only 10% of the city's black ministers join the campaign.) That evening: a mass meeting at First Baptist church. Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy run the meeting. William Kunstler is present as defense attorney. April 9, Tuesday: 25 blacks arrested at Bohemian Bakery Cafeteria and Britling Cafeteria. Sit-in at Loveman's Department Store includes arrest of a white picketer. Evening rally: Fred Shuttlesworth is out of jail and rallies the crowd. Martin Luther King speaks: "I had a dream tonight. A dream of seeing little Negro boys and girls walking to school with little white boys and girls, playing in the parks together and going swimming together." A group of white city leaders meet with SCLC leaders. No progress on issues raised in the "Birmingham Manifesto". April 10, Wednesday: Eight activists integrate Birmingham Public Library. No major disturbance. Police don't intervene. No arrests. 25 picketers arrested downtown and jailed. Black leaders push for boycott of white-owned businesses. At the Wednesday night rally, Martin Luther King calls for a new march on Thursday. Bull Connor and Chief of Police Jamie Moore get a temporary injunction from state circuit court judge W. A. Jenkins against marches, picketing, parades, etc. April 11, Thursday: Police serve Judge Jenkins' injunction on Movement leaders at the Gaston Motel. 12 arrested for picketing downtown. Birmingham whites and SCLC leaders meet a second time, but nothing comes of it. City informs local bail bondsman it will not accept bonds from him; the protestors have no way to raise bonds, and the Movement is out of funds. April 12, Friday (Good Friday): Movement leaders soul-searching; they're dispirited. Martin Luther King decides to lead a march and get arrested to gain publicity. Martin Luther King, Shuttlesworth and Abernathy lead the march (though Shuttlesworth steps out before arrest -- to leave one of them free to continue the protest).

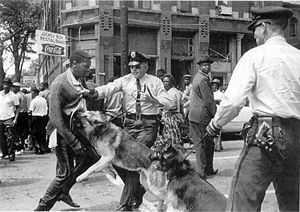

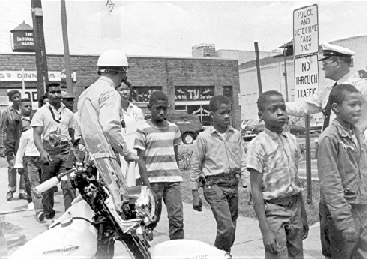

Police arrest 46, including Martin Luther King, Abernathy, singer Al Hibbler and a white college professor from nearby Miles College. Martin Luther King and Abernathy both land in solitary confinement. Only 308 attend the nightly rally. April 13, Saturday: Attorneys are finally allowed to speak to Martin Luther King in jail. Coretta King calls the White House, gets Pierre Salinger (the White House press secretary) who calls Bobby Kennedy, the attorney general. In Birmingham,12 arrested at spontaneous "stand-ins." Eight locally influential white ministers release a statement dubbed "A Call for Unity" condemning the protests, the methods, and involvement by outsiders. Note: The ministers' statement prompted Dr. Martin Luther King's "Letter from Birmingham Jail." In it, King says he had "almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to 'order' than to justice." King snuck out his writings on scraps of paper. Movement supporters typed them up, and they were edited by Rev. Wyatt Walker, executive director of SCLC, and his secretary. The "Letter" didn't get published for two months, though typewritten copies circulated in Birmingham through the spring. April 14, Sunday (Easter Sunday): A.D. King and others lead 30 marchers from Thirgood C.M.E. Church toward the Birmingham jail to pray for Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy, still locked away in jail. 2,000 spectators line the route; more arrests. April 15, Monday: President Kennedy calls Coretta King, and sends the FBI to Birmingham jail. Dr. Martin Luther King is allowed to call his wife for the first time since his arrest. At that night's mass rally, Rev. Wyatt Walker calls for a voter registration drive. Some call it an act of desperation; others argue it's a strategy to get the FBI directly involved. New mayor Boutwell and the new city council are sworn in, but the old mayor and council refuse to accept the election results . . . and refuse to give up their offices. The City of Birmingham now has two all-white governments. April 16, Tuesday: 9 more protesters arrested for picketing downtown. April 17, Wednesday: 150 blacks attend voter registration clinic at 16th St. Baptist Church. A group of protesters march from the church, and 17 are arrested. An additional 8 protesters are arrested for demonstrations at the Department of Justice Building. April 20, Saturday: Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy are released from jail on bond. Police arrest 15 protesters at downtown restaurants. April 23, Monday: Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy attend the evening rally, but there's little enthusiasm: only 10 volunteer to march; they raise $700 in the night's offering, compared to $7,000 the week before. April 24, Tuesday: Youth rally in the afternoon led by SCLC staff member James Bevel and two local disk jockeys. Youth swarm to a night meeting at St. James Baptist (it's the first standing room only gathering since Martin Luther King was jailed). King gets only 20 volunteers willing to march again . . . and most of these are youth recruited by Bevel. (Note: King didn't want to send out youth as marchers; he thought it should be adults only.) April 26, Friday: A white girl, daughter of a Methodist minister, participates in a lunch counter sit-in at Woolworths . . . she's "whisked out to safety." Judge Jenkins gives a "light sentence" to Dr. King and others charged with violating his injunction and issues a 20-day stay for appeals. April 27, Saturday: 9 black students are arrested for continuing protests. April 28, Sunday: White activists conduct kneel-ins at 39 local churches. A number of blacks who haven't been supporting the demonstrations meet to honor Rev. J.L. Ware, the leader of local blacks against ACMHR-SCLC. Rev. Ware had been working voter registration for years, but he didn't believe in the confrontational tactics advocated by Martin Luther King, Fred Shuttlesworth, and Ralph Abernathy. April 29, Monday: Martin Luther King convenes emergency meeting of ACMHR-SCLC central committee: he senses the movement is dying: no volunteers • national press are leaving town • publicity is drying up. James Bevel pushes for enlisting school students. King opposes. Bevel begins leafleting students for a meeting on Thursday. At the nightly rally, no students show up, but talk begins of a youth rally on Thursday. April 30, Tuesday: Martin Luther King leaves Birmingham for meetings in Atlanta. Birmingham city council denies SCLC a parade permit for a proposed march to city hall. At the nightly rally, Bevel leaks details of plans for student protests later in the week. May 1, Wednesday: Dr. King, Rev. Shuttlesworth, Rev. Walker, Rev. Abernathy back in Birmingham for the nightly meeting. May 2, Thursday: Under Bevel's leadership, 1,500 students skip school and march to different sites in Birmingham. 600 arrested, but without violence. Firemen are called out to help the police, but they don't use their hoses. 2,000 attend the evening rally. Martin Luther King and Fred Shuttlesworth come out in support of youth involvement. May 3, Friday ("Double D Day"): 1,000 students march. Firemen blast them with high-pressure hoses. Police sic dogs on them and beat some with billy clubs. Crowd pelts police and firemen with rocks and bricks. 250 arrested.

May 4, Saturday: Connor's police force disrupts a planned march by blocking students from leaving the churches. Students march anyway. More violence: firemen hose the marchers. 3,000 students rally in Kelly Ingram Park; adults cram the sidewalks, include several white spectators. 127 arrested. White businessmen and SCLC committees meet to negotiate. U.S. Department of Justice representative Burke Marshall flies in from Washington, representing Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and shuttles among groups trying to negotiate a truce, but no resolution reached. May 5, Sunday ("Miracle Sunday"): Largest protest march to date: as many as 3,000. Firemen block the streets with their hoses. Led by Rev. Charles Billips, the marchers kneel in the street . . . the firemen don't respond. Then, the marchers walk through the firemen's ranks. No arrests. No hose-down. Protestors perform "kneel-ins" at 13 white churches. Negotiations continue between SCLC and white leaders; no progress. May 6, Monday: Student rally empties the schools -- fewer than 900 of the school district's 7,500 black students attend class; of 1,337 students enrolled at one school, 87 blacks show up for class. 2,425 arrested, overfilling the jail. Arrested students are bused to the state fair grounds where some are housed in 4-H barracks, others outdoors in the rain. White businessmen and the SCLC meet, and negotiations continue with Burke Marshall. No resolution. Evening rallies at four churches draw thousands of protesters. May 7, Tuesday: 600 youths carpool into the central business district in the morning and close it down. As the temperature hits 87, afternoon demonstrations turn violent: fire hoses; dogs; a massive police force including men from surrounding communities beat back the spectators. Rev. Shuttlesworth hospitalized after being blasted by a hose into a brick wall. At day's end, 2,600 children remain locked up in jail and at the fair grounds.

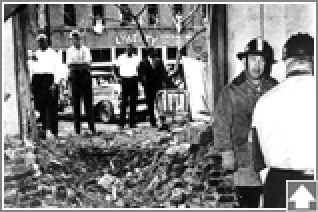

Gov. Wallace orders 250 state troopers to Birmingham; public safety director Al Lingo increases it to 600. They come armed with shotguns and submachine guns. The day's events bring extensive national press coverage. May 8, Wednesday: It's 90 degrees and steamy. After most-of-the night negotiations, city and SCLC committees call a motorium on demonstrations -- though Rev. Shuttlesworth angrily opposes it and criticizes Martin Luther King for selling out. King says give the city until 11 a.m. tomorrow to agree to our demands or we'll resume the marches. Judge sets appeal bonds for Martin Luther King, Ralph Abernathy and other leaders at $2,500 each. The heavy fines nearly torpedo the negotiated agreement, but A. G. Gaston posts bail for Dr. King and Rev. Abernathy. (Note: one long-term result: national unions put up $160,000 bail money for students, and the SCLC national office adds $90,000.) The evening rally draws thousands, including several rabbis and other whites. Participants say the 88 degree weather feels as oppressive as if it were 110 degrees. May 9, Thursday: Martin Luther King three times postpones a press conference to announce the negotiated agreement, and finally holds it in late afternoon . . . but the committees are still working on a final statement of agreement. No demonstrations today. May 10, Friday: Rev. Shuttlesworth announces an agreement, but critics say the black community won none of the Birmingham Manifesto demands. City officials refuse to endorse the agreement approved by the white businessmen's negotiating committee. May 11, Saturday: By daybreak, Gov. Wallace's state troopers pull out of Birmingham. 2,500 Ku Klux Klansmen hold an evening rally 13 miles south of Birmingham. May 12, Sunday (Mothers' Day): State troopers re-enter Birmingham at 2:30 a.m., this time with 100 troopers mounted on horseback. Someone bombs Rev. A.D. King's house and the A.G. Gaston motel. During the day, black neighborhoods erupt: 2,500 riot, burn stores, torch cars, pelt police and firemen with stones and bricks. President Kennedy orders 3,000 U.S. Army troops into Birmingham. Week of May 13-17: Nightly meetings continue. Floyd Patterson and Jackie Robinson attend the evening rally on Monday, May 13. May 20, Monday: The Birmingham Board of Education expels more than 1,000 students for earlier protests, including seniors who are then forced to go to summer school to get their diplomas. The NCAAP sues, but a judge upholds the school action. They appeal to the Fifth Circuit Court, get a restraining order, and the students return to school. May 21, Tuesday: The Alabama Supreme Court rules in favor of Birmingham Mayor Boutwell and his slate. It orders Bull Connor and his councilmen out of city hall. Connor's reign is over. May 22, Wednesday: 1,500 youths attend the evening's mass rally.

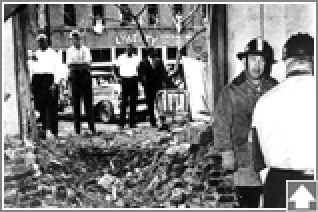

Key Events in late Summer and Fall

July 29, Monday: Black couples begin testing the City of Birmingham's recent outlawing of segregation at lunch counters. Despite the presence of National States Rights Party members (brown-shirted Nazis), no incidents occur. Note: this strategy of sending black couples to test the lunch counters continues at least through September 15. August 10, Saturday: Ku Klux Klan members burn down St. James Methodist, a church not involved in the movement. Note: this church had been burned down by the KKK in 1927.) August 19, Monday: Judge Allgood approves the new Birmingham schools desegregation plan -- it would admit no more than five blacks to any of the city's all-white schools. September 4, Wednesday: The house of Arthur Shores, Birmingham's most prominent civil rights lawyer, is bombed. Riots follow; 21 people injured. Policemen shoot and kill a 20-year-old black. Two black students are escorted to a previously all-white school and pick up their registration forms. White demonstrators jeer, throw rocks. Several whites arrested. September 15, Sunday (Youth Day): 16th Street Baptist Church is bombed at 10:22 a.m. Four girls, ages 11-14, are killed at Sunday School. The bombing draws international outrage and press coverage. Note: the two surviving suspects were sentenced to life in prison in 2001, and 2002 respectively.

September 25, Tuesday:

Two bombs explode on Center Street . . . the first at 1:34 a.m., the second 15 minutes later. The second is a shrapnel bomb designed to kill and maim people who rush to the scene of the first explosion -- a first for Birmingham. But there's no one around. No one is killed or injured..

Other selected Civil Rights events of the era

June 11, 1963, Tuesday:

Governor George Wallace blocks the school house door at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa to refuse admission to James Hood and Vivian Malone, it's first black students. On national TV, President Kennedy vows to push Congress to enact strong civil rights legislation.

Later that night, NCAAP field secretary Medgar Evers is murdered in Jackson, Mississippi.

August 28, 1963:

The March on Washington (for Jobs and Freedom): 200,000 people rally in front of the Lincoln Memorial in the country's largest Civil Rights demonstration. Martin Luther King delivers his famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

November 22, 1963: President John F. Kennedy assassinated. Lyndon Johnson becomes president. January 23, 1964: U.S. Congress ratifies the 24th Amendment, prohibiting poll taxes in elections for federal officials. July 2, 1964: President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964. August 4, 1964: The bodies of civil rights volunteers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner found under an earthen dam near Philadelphia, Mississippi. Participants in "Freedom Summer," a voter registration campaign led by Bob Moses of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), that brought a thousand volunteers to Mississippi, the three had disappeared after being arrested, then released, on June 23 on their way back from investigating the burning of a black church in Lawndale, Mississippi. August 20, 1964: President Johnson signs the Economic Opportunity Act into law, a major part of his "War on Poverty." It set aside nearly $1billion for programs to help the poor. December 10, 1964: Martin Luther King accepts the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway. March 7, 1965 ("Bloody Sunday"): Confrontation at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, at the start of the Selma to Montgomery Civil Rights march. 600 marchers repulsed by Alabama state troopers and local police, who then attack the marchers with clubs, tear gas, and electric cattle prods; dozens injured. March 21-25, 1965: Martin Luther King leads the march from Selma to Montgomery. 25,000 converge on Montgomery at the end of the march. March 28, 1965: Selma-Montgomery marcher Viola Liuzzo murdered while en route back to Selma. August 6, 1965: President Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965. August 11-16, 1965: Watts Riot: in Los Angeles, massive rioting is triggered by the arrest of a black man for drunk driving. 34 people killed; 3,000 arrested. July 10, 1966: Martin Luther King leads 5,000 protesters from a rally at Chicago's Soldier Field to city hall. October 1966: Bobby Seale and Huey Newton create the Black Panther party, Oakland, California. April 4, 1967: Martin Luther King delivers an anti-Vietnam war speech at Riverside Church in New York City. April 4, 1968: Martin Luther King assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. Note: the above information was compiled primarily from: Branch, Taylor Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988. Carson, Clayborne ("primary consultant") Civil Rights Chronicle. The African-American Struggle for Freedom. Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International, 2003. Eskew, Glenn T. But for Birmingham. The Local and National Movement in the Civil Rights Struggle. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997. McWorter, Diane Carry Me Home. Birmingham, Alabama. The Climatic Battle of the Civil Rights Struggle. New York: Simon & Shuster, 2001.

Return from Martin Luther King to Civil Rights Movement in 1963

Return to homepage

Enjoy this page? Please pay it forward. Here's how...

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment,

your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.

|

|

An excerpt from Soda Springs

Soda Springs in '63:

Flor views the barrio

They drove the dirt streets east of Main, four blocks by six, abutting the railroad tracks. The houses were crumbling adobe or flaking clapboard, tiny as summer cabins. Waist-high weeds overran empty lots and dirt front yards. Broken glass and rusted car bodies littered the place.

Flor recalled one squat whitewashed home trimmed in turquoise, its miniature lawn as manicured as a golf green. Roses and hollyhocks splashed its white picket fence with yellows and reds. This lone cheery home accentuated the fact that Mexican Soda Springs was a shabby slum.

Bobby’s parishioners called the Mexican enclave Beanville, or simply “over there.” No whites lived there. Only those with a pressing reason dared enter: police chief Zeigler, Doc Milard, volunteer firemen, an occasional road crew.

Flor had analyzed the 1960 Census: 932 Mexicans, fifty-eight percent of the town’s population, crowded like Third World refugees into twenty percent of the town’s land.

On the United Methodist side of Main, 675 whites lived in thirty blocks of bungalows and brick Queen Anne and Victorian homes with trees, shrubs, flowers, and grassy lawns, girded by sidewalks and paved streets. No Mexicans lived west of Main.

-- Soda Springs, Chapter 6

Meet Flor Hardwick in person

|